Why Accessible Assessments Matter: Jack’s Story

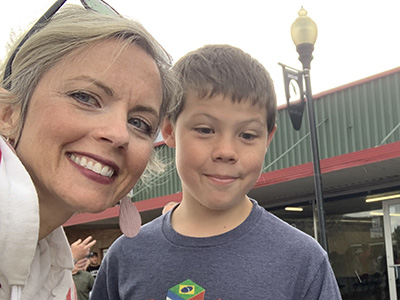

Guest Post

Every student deserves the chance to show what they know. That’s the whole point of state assessments: to measure progress, identify strengths and challenges, and help schools and states make informed decisions.

My son Jack is a dual media user, which means he reads and writes using both braille and enlarged print. Sometimes he is able, and prefers, to use his vision, but sometimes his eyes don’t give him reliable information. He can use braille if he needs to, but it’s not his preferred medium. For a long time, the state assessments he received weren’t in the right braille code and/or the equipment wasn’t in place for him to access the test in either enlarged print or braille.

When that happened, the test wasn’t really measuring what it’s supposed to measure. Instead, it was measuring how well he could read outdated braille codes, or how well his eyes worked, or for how long his eyes gave him accurate information. Case in point: In third grade, he took an assessment on the computer with enlarged print. While the main text was enlarged, the fill-in-the-blank answer options glitched out and ended up being half the size of the standard print, too small even for a person with normal vision to read. Another year, he was given testing materials in an outdated braille code instead of the code he had been taught.

State assessments are not fun as a whole; the process became really hard for Jack. Instead of showing his skills in reading and writing, it ended up showing only the barriers in front of him.

He knows that he’s different. He knows that he has to work harder sometimes because his eyes don’t work the same way as everyone else’s. When he isn’t given the chance to demonstrate what he knows, he finds it very disheartening.

To hear directly from Jack, I asked him to tell me about his experiences. Here’s what he said:

Jack [with confidence]: Mom, I know that I’m great at everything, I don’t need people to tell me that. It’s more the frustration. It’s not a fun way to spend my day, spending hours and hours on a test, missing class time that I’ll have to make up.

Sarah: Ok, what does an accessible test look like?

Jack: It’s a test that I can give reasonable answers to. It’s a test that I can do in a reasonable amount of time. If it takes me days and days to get my test done, it’s less accessible.

Sarah: In what ways have tests been inaccessible in the past?

Jack: The biggest way is that they take so long, like they take hours and hours to get through. And the zoom mechanics, zooming in and out, have been awful.

The Difference Access Makes

After seven years, Jack was finally provided with a test that was fully accessible. He could zoom in on the math problems, use UEB Grade 2 braille—the code he had been taught—for the reading portions, and was not timed out of questions. Although it still took nearly a full week, he was able to complete the test.

Now, Jack has assessments in his preferred learning medium. He’s able to sit down, take the test, and focus on the content—just like his peers. The test measures his reading, his comprehension, and his critical thinking. It doesn’t measure how well his eyes work, or whether outdated technology is standing in the way.

Jack gets the same practice tests and exposure to content as his classmates. His teachers and school now have accurate information about his progress. And most importantly, Jack feels like every other student sitting down to take the test.

Jack: Yeah, on that last EOC (End of Course Assessment), I got 100. Because I’m so smart. It was easy to figure out. The zoom worked.

That’s all he’s ever wanted: to be treated like everyone else. When he gets a grade, he wants to know that he earned it. He doesn’t want it handed to him because someone gave him the answers, and he wants a chance to show himself how smart he is.

When students learn differently, accessible assessments let us see whether they’re making the same progress as their peers. That information matters. It helps us know if students are learning the skills they need to become successful adults. Without access, the data from an assessment isn’t valid. What’s worse: from an administration level, his results may be flagged as inaccurate.

Jack: I think that’s going to come up more and more, that people think my test score was given to me, that someone helped me. I think especially in college people are going to think someone helped me. I’ve noticed that if you have special needs, and you are successful, it could be like – there are people who will say that the score was just given to you, instead of saying that you earned it.

Sarah: What makes materials accessible?

Jack: If the print is big enough, that makes it easier, especially in algebra.

No matter how big the print is, I’m going to be zooming in on it. So if the zoom doesn’t work or is weird, it will take longer, be more frustrating, and suck more. That’s one of the most frustrating things, when zoom is weird. Google slides is horrible. Google slides is an example of what not to do, in my opinion. For starters, when you zoom in on the slide show, it takes awhile. And, your cursor has to be in the right place, and then if you zoom in so far with the cursor in the wrong place, you get stuck.

Sarah: What about audio?

Jack: I don’t take a lot of tests auditorially. I think it would help if there were a big chunk of print or a long reading passage – it would help to do those auditorially.

Why It Matters

Whether a student uses braille, large print, assistive technology, or another form of access, the principle is the same:

- Accessible tests measure knowledge, not barriers. If a student can’t access the material, the test won’t measure learning.

- Straightforward systems help everyone. When publishers and states have a clear process for accessible materials, students get what they need, teachers get usable data, and states get reliable information.

- Equity leads to accuracy. Accessibility isn’t about special favors. It’s about making sure assessments do the job they were designed to do.

Sarah: If you could tell publishers or test makers, if you could give them some advice on how to make materials accessible, what are some pointers that you would make?

Jack: Make the zoom really easy. Breaking up those giant reading passages. In braille, making sure that there are no mistakes.

Looking Ahead

This fall, NCADEMI, in partnership with the OCALI AT&AEM Center, will be releasing new guidelines for the provision of braille for state assessments. These will be an important step forward for students like Jack who require timely access to assessments in high-quality braille format.

The goal should be simple: when a student sits down to take a test, the only thing being measured is their knowledge and skills. Not whether the materials arrived in the right format. Not whether the technology glitched. Not whether accessibility was an afterthought.

Accessible tests aren’t only about inclusion. They’re about accuracy, reliability, and fairness.

AI Is Not (Necessarily) Accessible

Guest Post

Many people became very excited about artificial intelligence (AI) at the end of 2022. AI existed previously, but mainly engineers and computer scientists knew about it. Different types of AI programs have different designs and do different jobs. The kind of AI that got people excited in 2022 was called a Large Language Model (LLM). It uses language that already exists in places like the internet. LLMs study language using math to learn patterns, then make new paragraphs and sentences. Besides LLMs that gather, study, and then make new language, other forms of AI exist. Most forms of AI involve learning from something existing, like photos or weather patterns.

Some educators and policy makers hoped AI would make learning on devices, such as mobile phones, tablets or laptops, more accessible for students with disabilities. Accessibility happens when students with disabilities can use the same materials in the same manner and at the same time as students without disabilities. For example, when students watch videos in class, the videos need captions so deaf students can learn. Since AI uses existing language to make more language, its programs can make captions for video. While captions made with AI programs might be better than having no captions at all, there can be limitations. For example, captions made with AI might not identity people’s names correctly. Also, because AI-generated captions might not recognize variations in how people speak English, they might not be understandable. Finally, when a system that uses AI thinks it is doing the right thing, it continues to do it without changing. Therefore, errors can be difficult to correct.

In addition, many educators are excited about chatbots that respond when asked questions. In school, many questions are about how to do tasks, such as “How do I find the slope of a line?” in math. Other tasks might be social or emotional, such as “How can I deal with stress?” When students need something explained more than once, a chatbot will repeat the language many times. These features of chatbots can support educators with personalizing learning and providing more immediate supports for students with disabilities.

Using AI at school has some potential to help students. However, it is important to remember that a product or service is not accessible just because it uses AI. The technology may not be able to interpret the words of people who speak differently from those whose language was used to build the program. For example, AI might not recognize the words of a student with a speech impairment. Some AI programs interfere with assistive technologies like screen readers, by blocking their use. Some AI programs cover the buttons that people use to customize for accessibility, such as color contrast. This makes the materials inaccessible.

The programs that use AI do not know whether the language they make is true or not. All the program can do is determine whether words are likely to occur in a specific order. LLMs can generate sentences that are grammatically correct and seem to be true, but they may not really be so. This can be a barrier to accessibility because some students with disabilities may need more time than students without disabilities to learn from the less-natural language made by AI. Schools that adopt AI programs for student use must be aware of such barriers and ensure accommodations are provided for students with disabilities.

What’s more, AI does not always check for truth and fairness. For example, if there are lies, misrepresentations, or unkind statements about people who have disabilities, that will be represented in language that is made by the program. This is an accessibility barrier because it costs time when students must confront and dismiss stereotypes to keep working.

Finally, many types of AI used in schools need new language all the time to keep functioning. One source of language for AI is the population of students who use it. AI programs use and store everything they are given. The programs keep personal information about family or geographic location, as well as information about individuals’ disabilities. Information is shared intentionally when a student says to a chatbot, “I have dyslexia.” Sharing also happens unintentionally. For example, a dyslexic student could enter language into a program, and the characteristics of dyslexia will show up in what they wrote. Schools do not always know what information is being collected and where it is going.

Disability advocates have warned that people with disabilities can be restricted in where they can work or live when information about them is made publicly available. Decision makers who access the information might discriminate. For example, an employer might be able to ask an AI program for information about a person as a prospective job candidate, and specific disability identification might be disclosed. Colleges or other education and training programs might also be provided information by AI programs that have been used by individuals with differences, and disabilities. That could happen if AI programs were trained with the social media posts, medical records, educational records, and/or previous employment records of a person with a disability. These disclosures might include direct naming of conditions and diagnoses or information that would help someone make an inference. A landlord might also access this type of information and not allow a person to rent a house. A bank might use it to deny a loan.

Educators need to ask questions about AI prior to using this technology with students with and without disabilities. Here are some examples of questions about accessibility and AI in schools:

- How do educators expect that AI will support learning of all students?

- How will AI affect the means of learning? The manner of learning? The time needed to learn?

- What information will be given to students about what AI is and what it does (and cannot do)?

- What steps are school leaders taking to protect students’ personal information and privacy?

- What alternatives do students have when they do not want to use AI programs at all, on a specific day, or for a specific task?

What are your questions about AI and accessibility for students with disabilities? Have you experienced any of the above examples? Please share your thoughts in the comments.