Braille Accessibility in State Assessments: Roles, Responsibilities, and Strategies

Publication Date: October 2025

Download PDF – Braille Accessibility in State Assessments: Roles, Responsibilities, and Strategies

Introduction

This guide is a joint publication of the National Center on Accessible Digital Educational Materials & Instruction (NCADEMI or “n-cademy”) and the OCALI AT&AEM Center. NCADEMI is funded by the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) at the U.S. Department of Education to improve the quality, availability, and timely provision of accessible digital educational materials and instruction for learners with disabilities, from early intervention through high school graduation. The AT&AEM Center is a centralized, responsive resource center that empowers individuals with disabilities by providing accessible educational materials, access to assistive technologies and highly specialized technical assistance and professional development support.

Supporting the participation of students with disabilities in state assessments is integral to the missions of both NCADEMI and the AT&AEM Center. The needs of students who rely on access for daily learning transfer to state and other large-scale assessment. As stated by OSEP, “Far too often, [students with disabilities] cannot use their accommodations or assistive technology (AT) on State-mandated tests due to issues with interoperability, privacy, and security concerns. These problems persist even when the AT is an approved device or resource” (Federal Register, Vol. 84, No. 148, Thursday, August 1, 2019, p. 37634).

This document presents a set of recommended guidelines to enhance the timely delivery and effective use of high-quality braille – embossed and electronic – and tactile graphics for state assessments. It builds upon earlier guidance provided in Improving the Provision and Use of Braille for State-Mandated Assessment by the National Center on Accessible Educational Materials (National AEM Center, 2023). The guidelines are consistent with the position of the Braille Authority of North America (BANA) on the requirement of accessible tests for braille readers (BANA, 2025). This document also addresses the need for individualized, appropriate accommodations required to accurately measure a student’s academic achievement and functional performance on state and districtwide assessments in alignment with section 612(a)(16) of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The intended audience for this resource is State Educational Agency (SEA) and Local Educational Agency (LEA) personnel responsible for ensuring the provision of accommodations on state assessments. Assessment vendors and Accessible Media Producers (AMPs), who are key partners in ensuring braille readers can access the state assessment, will also benefit from the information. Ideally, the guidelines will facilitate proactive planning and effective partnerships among these groups.

Section 1. Accommodations for Braille Users

Accommodations that are recommended for an individual on an IEP or 504 plan, including assistive technology (AT), are to be made available in both instruction and assessment situations to ensure appropriate access and consistent supports for that individual. Accommodations should be determined by an informed team, documented for the student, implemented during instruction, and consistently provided across all assessments, including informal, formal, districtwide, and statewide standardized assessments. When students do not have access to their accommodations or AT, they may experience unintended barriers completing assessments, and thus be unable to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and understanding. Removing access to these accommodations for testing purposes, or even requiring students to alter their regular accommodations, can have adverse effects on testing outcomes, and assessment results may be invalid. By implementing necessary accommodations, educators and testing administrators can help ensure that braille users have an accessible and fair testing experience.

Ensuring fair access to testing for braille users requires thoughtful accommodations that address multiple aspects of the assessment process. The use of one accommodation does not preclude the use of others. For example, a student may require both tactile and auditory accommodations. Braille users may require specific adjustments and accommodations within the following areas:

- Use of environmental accommodations

- Use of AT

- Use of accessible formats

- Use of accessible response methods

A. Use of environmental accommodations

Adjustments made to the student’s testing environment help create an accessible, supportive, and comfortable environment to meet the specific needs of the braille user. An environment that reduces possible barriers related to sensory overload and fatigue, as well as reduces anxiety, allows the student to focus on the test. The following are examples of types of environmental accommodations that a student may use (list not exhaustive):

- Extended time: Extended time provides additional time for the learner to read braille, process tactile information, navigate through testing materials using AT, and formulate responses without time constraints.

- Reduced distractions: Reducing distractions minimizes external stimuli and creates a quiet environment, helping the learner to maintain focus.

- Use of audio: In addition to reading braille, a student may benefit from audio versions of the test, and/or text-to-speech, and therefore require a quieter testing space.

- Reader: A human reader provides verbal access to allowable materials.

- Clarification of directions and graphics: A human reader can clarify and reread directions, particularly if braille layout changes presentation. A human reader can also clarify graphics and images, including pictures, tables, and graphs.

- Audio description: The verbal explanation of essential visual elements in a video or other multimedia resource, providing access to the visual content when the audio component alone is insufficient for perceiving on-screen actions.

- Small group or individual administration: External stimuli and distractions can be minimized when tests are administered individually or in small groups. This accommodation also allows for flexibility for breaks, testing pace, and access to AT, including audio versions.

- Adjustable lighting: Adjustable lighting reduces eye strain for students who have residual vision or light sensitivity. Lighting should be adjusted based on the student’s preference.

- Frequent breaks: Braille readers may require frequent breaks to prevent fatigue for lengthy periods, especially when the student may be using additional tactile materials.

These accommodations support the student’s sensory, cognitive, and physical needs. In the end, a supportive testing environment helps to ensure a student’s comfort and contributes to the student’s success in demonstrating their knowledge.

B. Use of AT

AT allows braille users to access test content and provide responses efficiently. To be effective, AT accommodations must align with both the student’s daily use and the technical specifications of the testing environment. AT accommodations must also consider compatibility with the testing interface, data stored on the device, and test propriety.

AT can be complex, and students spend a significant amount of time and energy learning to fluently use their AT. Requiring a student to use a similar yet unfamiliar AT (e.g., requiring the use of a stand-alone magnification tool rather than simple magnification with reflow inside a browser) can be disruptive and challenging. Even switching between comparable tools (e.g., using the JAWS screen reader vs. using the VoiceOver screen reader) can be more demanding and complicated than non-AT users might expect. The following are examples of types of AT that a student may use (list not exhaustive):

- Screen reader software: Converts on-screen text into synthesized speech and/or braille output (e.g., JAWS, NVDA, VoiceOver).

- Refreshable braille display: A device that allows students to read test materials in braille through tactile output.

- Braille notetaker: A portable device with braille input/output used for reading test materials and composing responses.

- Audio or digital calculator: Provides accessible mathematical tools when allowed, either through speech output or braille compatibility.

- Manipulatives: Provide access to content when visuals may be inaccessible; helpful with two- and three-dimensional graphics, particularly in mathematics and science.

- Speech-to-text: Supports written responses for students with additional motor or processing needs.

Students use AT to access the curriculum, learning environment, and assessments. Access to the student’s preferred AT contributes to student success in testing. Optimally, students can use the same devices/software in the assessment situation as they do in the instructional environment. Additionally, it is best practice for students to go into the assessment environment, prior to the actual assessment time, to practice the use of different devices and AT features to check for compatibility with the assessment platform. This will help reduce the risk of encountering barriers or glitches within the testing system during assessment.

C. Use of accessible formats

Braille comes in several formats suitable for specific reading levels and subject matter. Providing braille users with test materials in an appropriate, accessible format allows the student to demonstrate their knowledge, rather than their ability to access the test.

While the standardized braille code for reading and writing English used in the United States is Unified English Braille (UEB), UEB itself can be used in two distinct formats. An additional code specifically for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) can be used. Relevant braille formats in assessments promote equal access, foster independence, and accurately measure abilities, ensuring the right level of challenge and compliance with legal requirements and standardized testing protocols for accessibility. Understanding the differences between these formats is vital for educators, assessment vendors, accessible media producers (AMPs), and state agencies to ensure students receive appropriate accommodations.

State and district policies must clearly define requirements and compliance measures for assessment vendors and AMPs to meet all braille users’ needs, ensuring correct interpretation, consistency, and accurate measurement of skills. Using the IEP/504 to drive appropriate braille code decisions is the most effective way to certify that students’ specific needs are met, providing customized and consistent support that mirrors daily instruction. This approach also guarantees valid assessment results, fair comparisons, and adherence to legal mandates. The use of one format of accommodation does not preclude the use of others. For example, a student may require auditory accommodations to accompany a tactile format.

Specific format aspects for consideration include:

- Contracted braille vs uncontracted braille: Contracted braille (or Grade 2) is commonly used in educational materials to help students read more fluently and understand the text more quickly. Individuals new to braille may start with uncontracted braille (or Grade 1) before transitioning to the contracted form and may require double line spacing.

- Technical materials: Materials for STEM should be available in the technical code required by the student (i.e., UEB with Nemeth or UEB with Math/Science). See Appendix A for information about these two technical codes:

- UEB with Nemeth

- UEB Math/Science

- Tactile graphics: Braille tactile graphics are visual images created in tactile format using raised lines, shapes, and textures with accompanying braille labels. Tactile graphics may have limitations based on the complexity of the material and the skill, experience, and motor ability of the student. It is essential that all visuals used in assessment be accompanied by an audio or written image description regardless of the availability of tactile graphics.

- Image descriptions: Varying lengths and complexity of descriptions of images. See Appendix B for information about these two types of image descriptions:

- Alt text, which is a brief, textual description of an image designed to be read by screen readers and displayed if an image fails to load.

- Long description, which is typically used for complex charts, graphs, diagrams or tactile graphics that require additional context.

- Availability of a separate item bank optimized for braille: A separate item bank can help eliminate additional page turning or scrolling in lengthier assessment question sections.

- Digital access format: Tests to be accessed digitally on a braille display must use consistent formatting with structured elements such as headings, lists, and tables. Image descriptions must be provided. Accompanying hard copy braille tables and tactile graphics may provide additional access.

Testing materials provided in a suitable and accessible format for braille users allow students to engage with the content in a way that supports their ability to demonstrate what they know, rather than testing their ability to access the materials. By doing this, assessments become fairer and less biased.

D. Use of accessible response methods

Just as it is important for braille users to receive assessment materials in their preferred reading media and braille format, it is equally important that students have access to their preferred writing methods and tools. This ensures that the user can properly express themselves, review their own writing, and that the responses they provide are in their own words. Response methods should reflect the methods students use in their daily curricular work. The following are examples of methods that a student may use to provide testing responses (list not exhaustive):

- Writing in hard copy braille: Use of a Perkins Brailler, slate and stylus, or another manual writer

- Writing answers digitally: Use of a computer or braille notetaker with responses to be printed out after testing. Most braille notetakers and refreshable braille displays have an exam mode to disable non-essential functions, such as spellcheck.

- Providing answers orally: Use of a scribe for transcription of answers.

- Using standard digital test answering methods: Ability to complete various digital question formats, such as multiple choice, fill-in the blank, drag and drop, or short answer fields.

Accessible response methods and tools ensure the braille user can provide test responses in a way that best suits their preferences and needs. Note that all student-provided answers must be transferredverbatim into test-required answer formats (i.e., student response booklets or test delivery system).

Conclusion: Accommodations for Braille Users

The accommodations presented in this section are essential guidelines for both instruction and assessment to ensure equivalent access and valid measurement of braille users’ skills and knowledge. This section emphasizes that accommodations, including AT, must be consistently planned, implemented, and maintained across all settings to prevent barriers that could invalidate assessment results. Key areas addressed include creating an accessible environment, supporting the use of AT aligned with daily use, ensuring access to appropriately formatted materials, and offering accessible response methods that mirror students’ typical modes of communication. By prioritizing consistency, accessibility, and the student’s individualized needs, educators and testing administrators can provide supportive assessment experiences for braille users, while complying with legal and educational standards.

Section 2. Test Requirements and Components

Ensuring equivalent access for braille users on state assessments requires intentional, coordinated efforts across every stage of test development, production, delivery, and evaluation. Braille assessments must be designed to uphold high standards of accessibility, consistency, and fairness, allowing students who read braille to demonstrate their knowledge under conditions equivalent to their peers. This work involves the collaboration of State Educational Agencies (SEAs), Local Educational Agencies (LEAs), assessment vendors, and accessible media producers (AMPs), each playing a vital role in supporting accessible practices. Key components include:

- Review of assessment items by a fairness/bias committee.

- Production of braille and tactile graphics, including quality assurance reviews by certified transcribers and certified proofreaders.

- Use of MathML for interoperability with a variety of assistive technologies (AT).

- Evaluation that the test met the needs of braille users.

Together, these strategies form a comprehensive framework that ensures braille users have the tools and opportunities they need to fully engage with and succeed in state assessments.

A. Review of assessment items by a fairness/bias committee

It is important that assessment items are reviewed for potential bias or barriers that could put braille users at a disadvantage. A fairness and bias committee should be used to review potential assessment items. In addition to content experts, the committee should include individuals who read braille, members with expertise in braille literacy and accessibility, and those who understand braille users’ educational experiences. This ensures that assessments support equivalent access and valid results. To establish an effective and reliable fairness and bias review process, the following key actions should be taken:

- Specify credentials: Committee should ideally include certified Teachers of Students with Visual Impairments (TVIs), certified braille transcribers, braille readers, and accessibility experts.

- Conduct structured reviews: Items should be reviewed for accessibility, language, clarity, and bias related to braille use. Findings and recommendations for each item reviewed should be documented.

Implementing a fairness and bias committee with the appropriate expertise ensures that assessment items are accessible and free from unintended barriers.

B. Production of braille and tactile graphics

The accurate production of braille assessments and tactile graphics is essential for maintaining test validity and accessibility. Quality assurance processes must include reviews by certified braille transcribers who have experience with educational materials and the content being assessed (e.g., STEM subjects for tactile graphics). To achieve high-quality braille and tactile graphic production, the following practices should be implemented:

- Use Certified Braille Transcribers and Certified Proofreaders: Professionals with expertise in educational content and braille formats should be responsible for producing and reviewing materials.

- Comply with tactile graphic standards: Ensure graphics are simplified to support understanding without omitting essential information and verify they comply with the Braille Authority of North America (BANA) Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics.

- Use image descriptions: Graphics should include concise, meaningful descriptions. See Appendix B for clarification about when a description with or without a tactile graphic may be necessary.

- Follow accessibility standards: Digital materials should comply with the current version of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) at Level AA Conformance.

- Conduct quality assurance checks: Conduct multi-stage reviews: pre-production checks, post-embossing checks, and spot-checking for accuracy and readability.

- Align with grade level: Align braille materials, image descriptions and graphics with the grade-level expectations and content standards.

- Use appropriate transcriber notes: Notes should be brief and written at the appropriate grade level.

- Format braille materials properly: Using the most up to date version of the BANA Formats. The purchaser of the test and the vender/transcribing agency should fully agree on a consistent formatting style of testing materials such as headings, print page numbers, lists, directions, and exercises.

Ensuring that certified braille transcribers and certified proofreaders conduct quality assurance reviews enhances the accuracy, consistency, and usability of braille materials and tactile graphics, directly impacting braille users’ ability to access and engage with assessment content.

C. Use of MathML for interoperability with a variety of assistive technology

Mathematical Markup Language (MathML) is a coding language for describing mathematical and scientific content in a way that allows screen reader programs to accurately interpret, speak, and display content. MathML preserves the structure and meaning of mathematical content, ensuring that students who use screen reader programs can fully engage with digital materials.

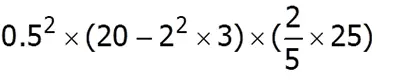

Here is an example of a higher-level math equation:

- Without MathML, a screen reader would read this content as a string of disconnected symbols: “0.5 superscript 2 end superscript times 20 minus 2 superscript 2 end superscript times 3 times 2 slash 5 times 25.”

- MathML allows this content to be read by a screen reader clearly in a style more like natural mathematical language: “Math content: 0.5 squared times left parentheses 20 minus 2 squared times 3 right parentheses times left parentheses two-fifths times 25 right parentheses.”

- Note: Each screen reader program is unique and has its own version of a math viewer that requires student knowledge of specific keyboard navigation commands to interact with the content.

The use of MathML is important for the following reasons:

- Accessibility: Enables screen readers and other assistive technology (AT) to interpret, read, and display mathematical and scientific content.

- Structure: Encodes the meaning and structure of math, making it easier to interpret, search, copy, and use.

- Compatibility: Accurately supports mathematical and scientific content with braille displays and text-to-speech programs.

MathML is important for both the braille user and developers for successful presentation of mathematical and scientific material. For students, it is critical for accessing digital math content including homework, textbooks, and assessments. For developers, it supports accessible math in various digital content formats that meet accessibility standards and work with various AT.

D. Evaluation that the test met the needs of braille users

Gathering and analyzing feedback ensures continuous improvement in assessment design, fairness, and administration. A post-assessment evaluation helps identify what worked well and what could be improved. Post-assessment evaluations must include a focus on whether the test materials, delivery, and accommodations effectively meet the needs of all students, including students who use braille. To ensure a thorough evaluation process, the following steps should be taken:

- Collect structured feedback: Gather input from students, teachers, and proctors about the accessibility and usability of braille materials and AT used.

- Analyze assessment data: Review performance data and patternsspecific to braille users to identify trends or barriers that may have affected their access or outcome.

- Review AT compatibility: Ensure that AT devices or software used during testing functioned properly and were compatible with the content.

- Review embossed tactile graphics: Examine the quality, clarity, and appropriateness of the graphics, as well as the request process used during the assessment.

- Revise assessments: Update assessment development protocols based on evaluation findings to improve future accessibility.

Conducting a data-informed evaluation process is important for maintaining high standards of accessibility and continuous improvement. The evaluation process should include whether braille users’ needs were effectively met. This provides essential information for refining assessments, improving accessibility, and ensuring fair measurement of students’ knowledge and skills.

Conclusion: Test Requirements and Components

The development, production, and evaluation of braille assessments require a comprehensive, detail-oriented approach that prioritizes accessibility, fairness, and continuous improvement. Through careful item review, high-quality braille production, the use of interoperable digital standards like MathML, and rigorous post-assessment evaluations, SEAs, LEAs, assessment vendors, and AMPs can work collaboratively to create assessments that truly reflect braille users’ abilities. These efforts ensure that braille users have fair opportunities to demonstrate their learning, upholding both educational excellence and legal obligations for accessibility.

Section 3. Administration of Assessments in Braille Format

State Educational Agencies (SEAs) play a crucial role in shaping the landscape of large-scale assessments, from standards and policies to best practices and procurement protocols. It is vital that SEAs consider their roles in working together, working within their state framework, and working with their Local Educational Agencies (LEA) to ensure that both paper and digital braille assessments are consistent, timely, and of high quality. Here are three critical areas to strengthen braille assessment development and implementation:

- Establish coordination and consistency across SEAs

- Provide clear state-level guidance to LEAs

- Deliver equivalent practice test opportunities for braille users

Together, these strategies support the delivery of timely, accessible, and instructionally aligned assessments, ensuring that braille readers can demonstrate their knowledge and skills under the same conditions as their peers. The following sections provide guidance on specific actions that SEAs can take to improve the development, delivery, and support of braille assessment materials.

A. Establish coordination and consistency among SEAs

Greater coordination among SEAs improves the quality, timeliness, and cost-effectiveness of braille assessment materials. By working collaboratively, SEAs can develop shared expectations and reduce duplication of effort and costs. Collaboration also ensures improved access for students who use braille by establishing clear, shared expectations and standards for assessment vendors, accessible media producers (AMPs) and LEAs. The following are examples of ways that SEAs can coordinate:

- Collaborate with partners: Work with other SEAs and national partners (e.g., National Braille Association (NBA), American Printing House for the Blind (APH), National Federation of the Blind (NFB), and American Council of the Blind (ACB)) to share similar challenges and solutions to promote better access.

- Improve braille quality: Develop and share standards, policies, and common definitions/frameworks. Align procurement and quality protocols to ensure consistency in braille production (paper and digital). Use certified braille transcribers and certified proofreaders, allow enough time for proofreading, and follow proper formatting guidelines.

- Create a shared item bank: Pool braille-optimized test items across states to support accessible materials for testing and content alignment.

- Support professional development: Create shared training opportunities for teachers and test administrators to ensure appropriate support for braille users.

- Share data and evaluation results: Exchange findings on practices, challenges, and student outcomes to refine and improve systems.

- Reduce costs: Create shared requirements and coordinate requests to assessment vendors and AMPs to lower costs and avoid duplication of effort.

Coordination among SEAs can significantly improve the quality, accessibility, and cost-efficiency of braille assessments. By developing and sharing common standards, policies, and best practices, SEAs can ensure that high-quality braille materials are produced and delivered on time. Collaborative efforts can also streamline assessment processes, enhance training and professional development, and reduce duplication of costs through shared assessment vendor expectations and pooled resources. Establishing a shared item bank and exchanging implementation data and research findings can also improve the accessibility of assessments for braille users. Additionally, partnerships with national organizations and participation in federal initiatives and joint conferences can strengthen interagency collaboration, foster innovation, and support continuous improvement across states.

B. Provide clear state-level guidance to LEAs

To effectively implement assessments and accommodations for braille users, LEAs depend on guidance from their SEAs. SEA-developed guidance documents are vital resources that not only clarify legal obligations but also provide practical, step-by-step processes for ensuring that braille users receive the necessary materials, technologies, and accommodations during assessments. The following are examples of ways that SEAs could provide guidance for LEAs:

- Clarify roles and responsibilities: Clearly define what LEAs must do to support braille assessments, including identifying eligible students, ordering materials, and planning for assistive technology (AT) needs.

- Maintain open communication: Establish consistent outreach with districts through newsletters, listservs, training sessions, virtual office hours, or help desks to answer questions and provide technical assistance.

- Ensure timely student identification and materials ordering: Provide timelines and checklists to help districts identify braille users early, procure necessary resources well before assessment windows, and allow time for preparing supplemental materials before the assessment window opens.

- Support implementation: Share best practices, provide training for teachers and administrators, and offer resources for support.

- Guide AT use: Include directions on using and approving AT devices during testing, including the process for requesting use of external tools. This could be provided through resources such as accessibility manuals (e.g., Ohio’s Accessibility Manual).

When SEAs provide guidance and professional development, LEAs can fulfill their responsibilities more effectively. SEA-issued guidance documents play a critical role by outlining legal responsibilities and offering practical steps for identifying students who need braille, ordering appropriate materials, and preparing for the use of AT. Effective SEA support includes defining LEA roles, maintaining open lines of communication, providing timelines and planning tools, sharing best practices, and offering detailed instructions on the use of AT. Together, these strategies help LEAs ensure that braille users receive the materials and accommodations they need for equivalent access to statewide assessments. Through this collaboration, students who require braille assessments receive the appropriate support, aligned with their instructional practices.

C. Deliver equivalent practice test opportunities for braille users

Students who use braille must be given opportunities to familiarize themselves with test materials and formats in ways that reflect their everyday learning experiences. Providing equivalent practice opportunities reduces test barriers, improves access, and supports more valid assessment outcomes. The following actions should be taken by SEAs and LEAs to align practice opportunities with instructional practices and testing conditions:

- Align practice tests with instruction: Practice materials should reflect the same supports, technologies, and content structures that will be used during the assessment (e.g., braille notetakers, refreshable braille displays, tactile graphics, manipulatives, hard copy braille).

- Use real testing media and supports: Provide access to practice with tactile graphics, refreshable braille displays, and braille notetakers.

- Include appropriate braille codes and formats: Offer materials in UEB with Nemeth or UEB Math/Science braille when required for content areas like math and science. Materials may also need to be provided in uncontracted or contracted braille as appropriate to the learner’s needs.

- Prepare environments and technology: Allow students to use their own devices and test accommodations in advance of the assessment to verify compatibility and readiness and to help avoid testing-day issues.

- Offer fixed-form and pre-embossed options: Reduce logistical barriers during test administration by preparing materials ahead of time.

To fully prepare braille users for state assessments, practice tests and opportunities need to closely reflect the conditions of the actual assessment. This includes the same supports and accommodations, technologies, content structure, and appropriate braille codes that will be used during the assessment. When these strategies are implemented during daily instruction and practiced in a testing setting, they help eliminate access barriers, support student confidence, and lead to more accurate assessment outcomes.

Conclusion: Administration of Assessments in Braille Format

The development and administration of braille assessments require intentional collaboration, clear guidance for state and local levels, and equivalent practice opportunities to ensure all students who use braille can fully access and engage with state assessments. SEAs play a pivotal role in leading this work through coordinated efforts that enhance consistency, reduce duplication, and elevate the quality of braille materials across states. Providing clear guidance to LEAs, SEAs help ensure that braille accommodations are implemented accurately and in alignment with instructional practices. Additionally, offering braille users the opportunity to engage in meaningful and aligned practice tests helps reduce barriers and supports valid assessment outcomes. Together, these strategies form a comprehensive approach that allows braille users to demonstrate their knowledge and skills.

Section 4. Supportive Roles

Providing braille support within the different areas of need is not the responsibility of a single person or team. It requires shared ownership and collaboration among State Education Agencies (SEAs), Local Education Agencies (LEAs), assessment vendors, and accessible media producers (AMPs). This section outlines the responsibilities of each group and how they can work together to create accessible assessments for all braille users:

SEA Roles:

- Leadership and coordination: Set policies, standards, and procurement protocols for braille assessments and ensure consistency across districts. Establish clear, statewide policies for accessible assessments, including braille format requirements (UEB with Nemeth and UEB Math/Science) and accommodation use. Establish timelines and checklists for early student identification and material ordering. Provide training and resources for LEAs on selecting and documenting appropriate accommodations. Recommend practice opportunities for students to use familiar assistive technology (AT) and assessment tools.

- Collaboration: Partner with other SEAs and national organizations to share resources, reduce duplication, and improve quality. Facilitate multi-state collaboration with national organizations (e.g., National Braille Association (NBA), American Printing House for the Blind (APH), National Federation of the Blind (NFB), and American Council of the Blind (ACB)). Create and share a braille-optimized item bank across states. Share implementation data, evaluation results, and best practices with other SEAs.

- Guidance and support: Provide LEAs with clear guidance on roles, timelines, material ordering, and AT use. Promote understanding of braille codes and tactile graphics among educators and assessment vendors.

- Professional development: Offer shared training and resources for educators and test administrators.

- Evaluation and quality assurance: Oversee post-assessment evaluations and continuous improvement efforts, including data analysis and assessment vendor and AMP accountability. Ensure appropriate image descriptions are provided (both digital alt text and hard copy braille). SEAs and LEAs should require that image descriptions be written by content authors who understand the purpose and context of images used in the test materials.

- Practice test access: Ensure practice tests mirror real testing conditions, technologies, and content formats for braille users. Offer fixed-form or pre-embossed braille practice test options to reduce logistical issues.

LEA Roles:

- Implementation: Identify eligible braille users, order materials, and ensure students are prepared with necessary accommodations and AT. Prepare assessment environments and technology access in advance. Implement SEA-provided models for accommodations and technology integration.

- Communication: Maintain ongoing communication with SEAs to receive updates, resources, and support. Work with SEAs to clarify policies and communicate with assessment vendors to meet student needs, including ensuring the proper braille code is requested.

- Teacher training and readiness: Provide staff training and ensure students have practice opportunities in the actual testing environment. Ensure accommodations and AT used during instruction are also available during assessments. Facilitate student practice with appropriate braille materials, technologies, and testing environments–in advance. Provide environments with appropriate space, time, staffing, and technology for accessible assessments. Participate in evaluations to share outcomes and experiences to help inform needed revisions.

- Compliance: Follow SEA guidelines to ensure timely, accessible, and equally effective assessment delivery for students who use braille. Follow SEA guidance regarding roles and responsibilities for braille assessment support. Document accommodations clearly in IEP/504 plans, including specific braille formats and AT.

Roles for Assessment Vendors and AMPs:

- Production and formatting: Produce high-quality braille and tactile graphics using certified braille transcribers and certified proofreaders and follow Braille Authority of North America (BANA) and Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 Level AA standards. Align production of braille assessments with SEA-developed standards, definitions, and quality protocols. Be prepared to produce all assessment materials in both UEB with Nemeth and UEB Math/Science formats, as required by student plans and content areas. Provide accessible image descriptions for all visuals, including tactile graphics, following best practices. Ensure accurate and timely production of both paper and digital braille assessments.

- Technology compatibility: Ensure digital content is accessible via AT and use MathML for math and science content. Ensure assessment platforms and materials meet WCAG 2.1 AA and test for compatibility with a wide range of AT (e.g., screen readers, braille notetakers, speech-to-text tools).

- Quality assurance: Conduct multi-stage reviews (pre-production, post-embossing, spot-checking) to ensure accuracy and readability. Develop accessible practice test materials that reflect real assessment conditions. Participate in user testing and incorporate feedback from educators and end users to continually improve product accessibility.

- Collaboration with SEAs: Align with SEA standards and timelines to ensure timely delivery and accessibility of braille materials. Understand and apply state policies regarding braille and accessible materials. Collaborate with SEAs to integrate braille-optimized items into shared item banks.

Acknowledgements

NCADEMI is grateful to the following experts who served on the original workgroups (2022-2024) and in the most recent development of the guidelines presented in this document:

- Michael Cantino, BVIS Technology Professional Development Specialist, Northwest Regional Education Service District

- Erica Chambers, AT&AEM Specialist, AT&AEM Center, OCALI

- Sarah Chatfield, CEO, SBES, Inc

- Frances Mary D’Andrea, Program Coordinator, Visual Impairment & Blindness, Department of Teaching, Learning & Leading, University of Pittsburgh

- Rick Ferrie, RDFRush Consulting, LLC

- Jen Govender, AT&AEM Specialist, AT&AEM Center, OCALI

- Richard Jackson, Professor, Lynch School of Education and Human Development, Boston College

- Kathy Kremplewski, Braille and Accessible Assessment Specialist, Florida Instructional Materials Center for the Visually Impaired

- Shelley Mack, Braille Consultant, AT&AEM Center, OCALI

- Nancy Moulton, Program Director, Education Services for Blind and Visually Impaired Children, Catholic Charities of Maine

- Kristin Oien, Specialist for the Blind / Visually Impaired, Minnesota Department of Education

- Katherine Padgett, Accessible Test Editor, American Printing House for the Blind

- Katie Robinson, AEM Production Specialist, AT&AEM Center, OCALI

- Rachel Schultz, Program Director, Center of Excellence on Instructional Practice, OCALI

- Adrienne Shoemaker, TVI/APH Scholar, New Hampshire Department of Education

- Stacy Springer, Program Director, AT&AEM Center, OCALI

Contact NCADEMI and the AT&AEM Center

Please reach out to NCADEMI and the AT&AEM Center at OCALI for support with implementing the guidelines presented in this resource.

NCADEMI

- Website: https://ncademi.org

- E-mail: ncademi@usu.edu

- Voice or Text: (435) 554-8213

AT&AEM Center at OCALI

- Website: https://ataem.org/

- E-mail: ataem_info@ocali.org

- Voice or Text: (614) 410-1042

References

Braille Authority of North America (2025, May). Accessible Tests are Required for Braille Readers. A Position Statement. https://www.brailleauthority.org/bana-releases-new-position-statement-accessible-tests-are-required-braille-readers

National Center on Accessible Educational Materials at CAST (2023). Recommendations for Improving the Provision and Use of Braille for State-Mandated Assessment. Lynnfield, MA: Author.

Recommended citation

National Center on Accessible Digital Educational Materials & Instruction. (2025, October). Braille Accessibility in State Assessments: Roles, Responsibilities, and Strategies. Logan, UT: Author. Retrieved [insert date] from https://ncademi.org/resources/publications/braille-assessment

Appendix A. UEB Math/Science vs UEB with Nemeth

While the standardized braille code used in the U.S. for reading and writing English is Unified English Braille (UEB), materials for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) can be written in two distinct ways: UEB Math/Science and UEB with Nemeth. Understanding the differences between these formats is vital for educators, assessment vendors, accessible media producers (AMPs), and state agencies.

The term UEB Math/Science (also UEB technical) describes the basic UEB code to represent and transcribe STEM materials. UEB was developed to unify various braille codes previously used for different content (e.g., literary, mathematical, and technical) into one standardized system for English. It can accurately express STEM materials.

UEB with Nemeth refers to the primary use of UEB while using Nemeth Code, a braille code specifically designed for the representation and transcription of STEM materials for technical content. Nemeth Code provides a comprehensive system for expressing complex equations and scientific content with its own distinct set of symbols. The Braille Authority of North America (BANA) has developed guidelines for the use of Nemeth within the UEB code. Code switching indicators are employed to prevent any ambiguity or conflict between UEB and Nemeth symbols.

Many states and district accessibility and accommodation policies provide guidance on which braille code to use, and most states allow for both UEB Math/Science and UEB with Nemeth. The decision often depends on the student’s needs (e.g., transfer student, student is more fluent with one code over the other). The student’s IEP/504 Plan should document the selected code to be used for both daily work and assessments. Using the IEP/504 Plan to drive appropriate braille code decisions is the most effective way to certify that students’ specific needs are met, providing customized and consistent support that mirrors daily instruction. This approach also guarantees valid assessment results, fair comparisons, and adherence to legal mandates. The availability of technical materials in both UEB Math/Science and UEB with Nemeth via IEP/504 team recommendations is essential for providing equally effective educational opportunities for students who are braille users. Assessment vendors/publishers should be ready to provide both forms of technical material in braille. State and district policies must clearly define requirements and compliance measures for vendors to meet all braille users’ needs, ensuring correct interpretation, consistency, and accurate measurement of skills. SEAs and LEAs must be diligent in ensuring the proper braille code is requested as differences in vendor wording and descriptions may cause confusion (e.g., UEB Math/Science vs. UEB Technical).

Appendix B. Best Practices for Image Description

Every visual that conveys information necessary for answering a question should be described clearly and appropriately in text. If an image does not convey content needed to answer a question, it may be considered decorative. A decorative image does not contribute meaning and is typically used for layout or non-informative purposes. The information provided by the image might already be provided within the text or the image might be included to make the page more visually attractive. Additionally, a decorative image is one that does not have a function (e.g., it is not a link).

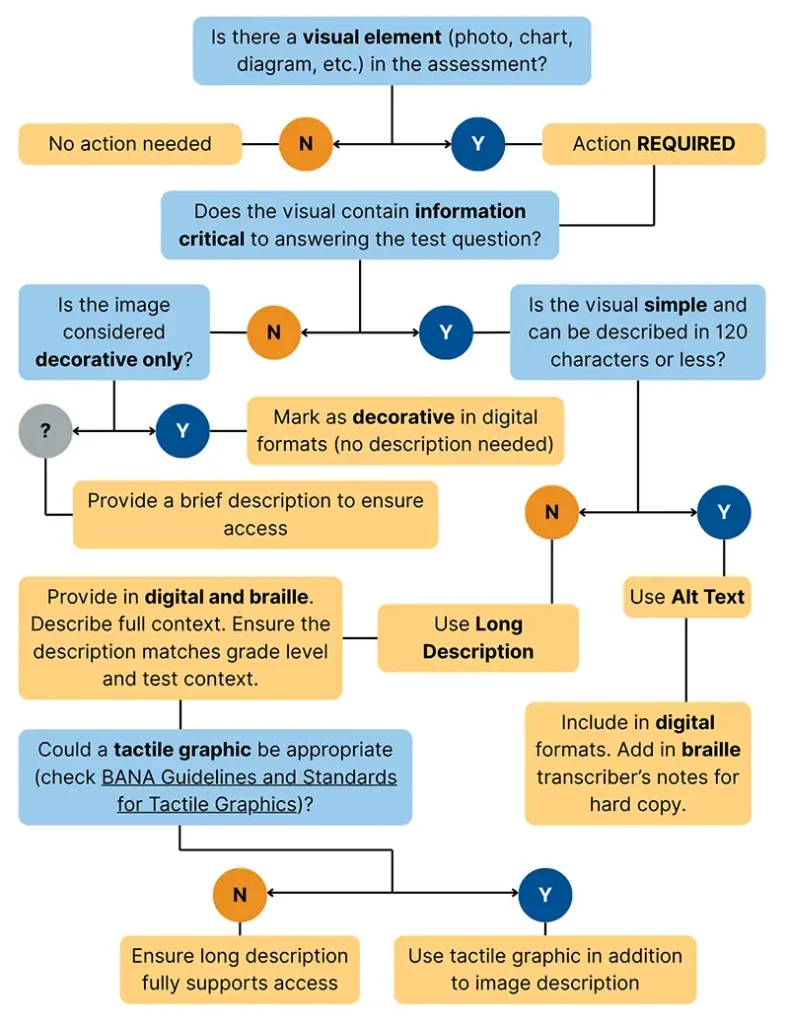

Use the following series of questions as a guide to determine the appropriate method for providing image descriptions in assessments. Figure B-1 provides an alternative flowchart representation.

- Is there a visual element (photo, chart, diagram, etc.) in the assessment?

- Yes: Proceed with the next question.

- No: No action is needed for alt text or image description.

- Does the visual contain information critical to answering the test question?

- Yes: Description is REQUIRED. Proceed to the next question.

- No: Consider if the visual is decorative:

- If decorative, mark as decorative in digital formats (no description needed).

- If uncertain, provide a brief description to ensure access.

- Is the visual simple and can be described in 120 characters or less?

- Yes: Use alt text.

- Include in digital formats.

- Add braille transcriber’s notes for hard copy.

- No: Use long description and consider the need for a tactile graphic (next question).

- Provide in digital and braille. Describe full context. Ensure description matches grade level and test context.

- Yes: Use alt text.

- Could a tactile graphic be appropriate (check BANA Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics)?

- Yes: Use tactile graphic in addition to image description.

- No: Ensure long description fully supports access.

Examples of Image Descriptions

View examples of various image descriptions through the following resources:

- Section 6 of the BANA Braille Formats Principles of Print-to-Braille Transcription manual provides detailed guidelines for transcribing illustrative materials, such as photographs, maps, charts, and diagrams, into braille, emphasizing tactile graphics, standardized formatting, and descriptive clarity to ensure accessibility for braille readers.

- The DIAGRAM Center’s Image Description Guidelines provide a comprehensive reference for creating accessible image descriptions, offering general best practices and specific techniques tailored to various image types and content areas to support individuals who are blind or visually impaired.

- WGBH’s Effective Practices for Description of Science Content – Guidelines for Describing STEM Images provides guidance for specific types of images. Although developed for science content, the guidelines are relevant to other subject areas.

Figure B-1: Decision-Making Flowchart for Image Descriptions

Appendix C. Glossary

- Accessible

- A widely accepted definition of “accessible” comes from the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Department of Education: Accessible means “an individual with a disability can access the same information, engage in the same interactions, and otherwise participate in or benefit from the same services, programs, and activities as individuals without disabilities, in a manner that provides substantially equivalent timeliness, privacy, independence, and ease of use.” An original version of this statement appeared in a 2010 joint Dear Colleague Letter to university presidents regarding the adoption of non-accessible technology. References to student privacy and independence were added in the 2024 ADA Title II Final Rule.

- Accommodation

- An allowed adjustment or alteration to a curriculum or assessment that provides access for a student with a disability. An accommodation does not change what a student is expected to master; rather, it provides access. The learning or assessment objective remains intact.

- Alt Text

- A brief textual description of an image, designed to be read by screen readers and displayed if an image fails to load.

- Accessible Format

- Under U.S. copyright law, an “accessible format” is “an alternative manner or form that gives an eligible person access to the work when the copy or phonorecord in the accessible format is used exclusively by the eligible person to permit him or her to have access as feasibly and comfortably as a person without such disability.” In other words, an accessible format is an alternative presentation of information that provides access to otherwise inaccessible materials for individuals with disabilities.

- Accessible Media Producer (AMP)

- Agencies, organizations, or other services that convert materials, including textbooks, related curriculum materials, and assessments, to one or more student-ready accessible formats.

- Assessment Vendor

- Organizations approved by state educational agencies (SEAs) to develop, administer, and score standardized tests that meet federal and state accountability requirements for state testing in K–12 education.

- Assistive Technology (AT)

- An AT device is defined under Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) as “any item, piece of equipment, or product system, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of a child and specifically excludes a medical device that is surgically implanted or the replacement of such device” (e.g., a cochlear implant). AT devices are often viewed on a continuum of low-tech (e.g., a pencil grip), mid-tech (audio book), or high-tech (e.g., dynamic communication device). Certified Braille Transcriber and Certified Proofreader The Library of Congress, through the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled, individuals through graded courses and final assessments overseen by the National Federation of the Blind to transcribe printed material into braille. Certifications include Literary Braille, Mathematics Braille, and Music Braille Transcribing as well as Literary Braille and Mathematics Braille Proofreading.

- Contracted Braille (Grade 2)

- Contracted (or Grade 2) braille employs abbreviations and contractions for common words and letter combinations to improve reading speed and efficiency, while uncontracted (or Grade 1) braille uses a direct, letter-by-letter translation. The terms Grade 1 and Grade 2 refer to the use of braille contractions and not educational grade level.

- Fairness/Bias Committee

- A group of experts tasked with ensuring that assessments are fair and unbiased for all test-takers, regardless of their characteristics, by reviewing test content, identifying potential bias, and recommending revisions to ensure equally effective treatment and valid interpretations of scores.

- Image Description

- Any text description of a visual (e.g., graphic, image, table, or chart). The term is sometimes used interchangeably with alt text and long description. In this guide, we use “image description” as a general term, and “alt text” and “long description” to describe specific methods of describing images. Refer to Appendix B for more information.

- Local Educational Agency (LEA)

- A public board of education or other public authority legally constituted within a State for either administrative control or direction of, or to perform a service function for, public elementary schools or secondary schools in a city, county, township, school district, or other political subdivision of a State, or for a combination of school districts or counties as are recognized in a State as an administrative agency for its public elementary schools or secondary schools. (Source: IDEA Sec. 303.23)

- Long Description

- An image description that requires a longer description than alt text. These are typically used for complex charts, graphs, diagrams or tactile graphics that require additional context. Refer to Appendix B for more information.

- MathML

- Mathematical Markup Language (MathML) is an XML-based language used to encode mathematical notation and content for use on the web and in other applications, ensuring correct display and accessibility for assistive technologies.

- Perkins Brailler

- A manual braille writing machine used to produce raised braille on paper.

- State Educational Agency (SEA)

- The State board of education or other agency or officer primarily responsible for the State supervision of public elementary schools and secondary schools, or, if there is no such officer or agency, an officer or agency designated by the Governor or by State law. (Source: IDEA Sec. 300.41)

- Tactile Graphics

- Graphics that convey non-textual information through touch to people who are blind or have low vision. These may include tactile representations of pictures, maps, graphs, diagrams and other images. Students who are blind or visually impaired touch these raised lines and surfaces to access the same information as students who are sighted.

- Uncontracted Braille (Grade 1)

- Uncontracted (or Grade 1) braille uses a direct letter-by-letter translation, while contracted (or Grade 2) braille employs abbreviations and contractions for common words and letter combinations. The terms Grade 1 and Grade 2 refer to the use of braille contractions and not educational grade level.

- Unified English Braille (UEB)

- A braille code standard developed to unify the representation of literary and technical materials across the English-speaking world, aiming for consistency and clarity.

- UEB Math/Science

- The application of Unified English Braille (UEB) to represent and transcribe technical material from the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. This is sometimes referred to as “UEB technical.” The alternative to using UEB Math/Science is using UEB with Nemeth, Nemeth Code being a braille code specifically designed for technical notation. Refer to Appendix A for more information.

- UEB with Nemeth

- Nemeth Braille Code for Mathematics and Science Notation is a braille code specifically designed for representing materials from science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. Nemeth Code is used within the context of UEB. The alternative to using UEB with Nemeth is UEB Math/Science. Refer to Appendix A for more information.

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

- Technical standards developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) to make websites and other digital materials accessible for individuals with disabilities. The minimum standard required by the is , Level AA. WCAG defines three levels of conformance: “A” (lowest), “AA” (more comprehensive), and “AAA” (highest and often considered aspirational).